My longtime readers may remember that I wrote a lot about the Monuments Men in the early days of this blog. For those of you who weren’t with me back then, the Monuments Men was a small group of Allied service men and women who worked to protect monuments, fine art, and archives during World War Two. Officially, this group was known as the Monuments, Fine Art, and Archives Section, or MFAA, but they’re colloquially and more commonly known as the Monuments Men. The job of the Monuments Men was twofold. During the war, they protected monuments, fine art, and archives from damage and destruction. After the war, they tracked down all the art the Nazis had stolen and return it to its proper owners. This last job continues to the present day.

The Monuments Men became really popular in the public imagination (and also in mine) because of a 2014 movie starring George Clooney, Matt Damon, and Cate Blanchett in a fictionalized version of the real Monuments Men story. The Monuments Men movie was inspired by a wonderful book of the same name by Robert Edsel. The book tells the true, non-fiction version of the story, and I own two copies. To learn more about the Monuments Men, read my 2014 article for HeadStuff.

The sobriquet “Monuments Men” is somewhat inaccurate, because the MFAA included quite a few women. However, people usually only talk about one of them – a heroic Frenchwoman named Rose Valland. Valland was a true hero with a thrilling spy story, but she wasn’t the only woman at the table. I’m here today to talk about another one, British-American monuments officer Edith Standen.

Edith Appleton Standen (1905-1998) was born in Canada to a British father and an American mother. She grew up in the United Kingdom and graduated from Somerville College, Oxford. She studied English but was more interested in art and archaeology. After graduating, she moved to the United States and settled in Boston with her mother’s family. Her first job was at her uncle’s Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities.

Fortunately for Standen’s future museum career, her Boston relatives knew and introduced her to Paul Sachs, director of Harvard University’s Fogg Art Museum. At the time, Sachs was teaching a celebrated series of graduate courses about museum curatorship. Museum studies classes are now common, but Sachs’s was the very first. Sachs had a huge influence on 20th-century America’s significant museum directors and curators, most of whom had taken his classes. Sachs invited Standen to join the class despite not being officially enrolled at Harvard.

Through her Sachs connections, Standen was soon hired as secretary to Joseph E. Widener’s major Philadelphia art collection. She worked there for over a decade, until Widener donated everything to the National Gallery in 1942. Standen said that the bulk of her early art historical experience came from spending more than ten years with this collection.

Just after the United States entered World War Two, Standen assisted in moving Widener’s collection to Washington, then joined the Women’s Army Corps. She had recently become a U.S. citizen. Thanks to her art experience and Sachs connection, she was assigned to the MFAA and headed over to Europe in 1945. She attained the rank of Captain and was later awarded a Bronze Star.

After several over posts, Standen was eventually assigned to the Wiesbaden Collection Point. This was one of three facilities that Allied forces set up to deal with the unimaginable quantities of artwork recovered from secret Nazi storage locations. (All three collection points were in Germany; the other two were Munich and Offenbach.) She managed the Wiesbaden Collection Point from 1946-47. The work to be done in Wiesbaden was immense. The collection point received artworks recovered from Nazi stashes in places like Neuschwanstein Castle in Bavaria and Alt Aussee salt mine in Austria, often at a faster rate than staff could process them. Monuments officers and civilian volunteers photographed each artwork, assessed its condition, performed conservation treatment if necessary, identified objects (usually through research in makeshift art libraries), and figured out what country each work should be returned to. Collection point staff also had to arrange for the safe storage and transport of each artwork at a time when resources in Europe were very scarce. While the tasks sound impossibly difficult, imagine the spectacular artworks that Standen and her fellow monuments officers got to surround themselves with! It’s no wonder that she was set up for later museum-world success. Wiesbaden Collection Point was in the Wiesbaden Museum building, which is still an art museum today. Fittingly, it was the destination for many artworks from German museums, especially from the state museums in Berlin.

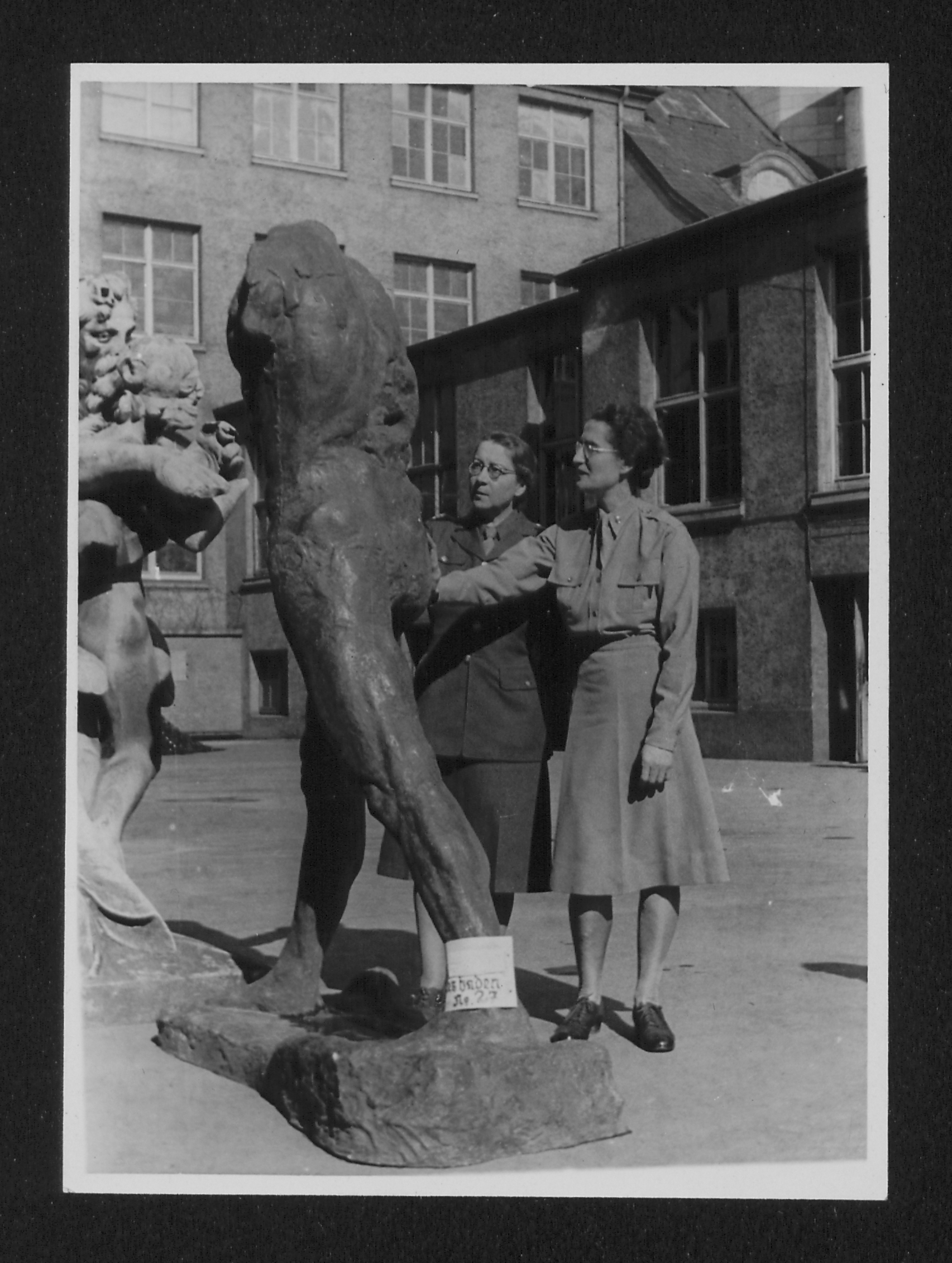

At Wiesbaden Collection Point, Standen worked alongside the most famous female monuments officer – Rose Valland. After the liberation of Paris and the end of her art spying, Valland came to work at Wiesbaden. Sources say that she and Standen became close friends, and numerous photographs of these two women together would seem to back this up. In Europe, Standen also worked with James Rorimer, future director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and her future boss.

During her time at Wiesbaden, Standen and other monuments officers took a stand on behalf of endangered artworks. In the fall of 1945, U.S. General Lucius Clay ordered that some of the German museum-owned artworks housed at Wiesbaden should be shipped to the National Gallery in Washington D.C. for “safekeeping”. Basically, he wanted to steal the artworks for the U.S., although this went against everything that Supreme Commander of Allied Expeditionary Forces Dwight D. Eisenhower believed in. Everybody in the MFAA was shocked and horrified, since this is exactly how the Nazis had justified their art thefts in the first place, but nobody could do anything about it. Officers came to Wiesbaden to collect over 200 objects, including masterpieces by Rembrandt and Raphael. Standen and her staff resisted the order but were “threatened … with court martials” (McWhinnie 28) if they didn’t comply.

Shortly thereafter, at the behest of Captain Walter I. Farmer, who had originally organized the Wiesbaden Collection Point, thirty-two MFAA officers signed a five-paragraph protest of these orders, known as the Wiesbaden Manifesto. Standen not only signed the manifesto but also continued to distribute copies and to campaign for its tenets in the following weeks. The manifesto had little effect at first. Two hundred and two German-owned objects were, in fact, shipped to the National Gallery, from which they went on a 13-city tour of the United States. However, popular pressure and press critique of their removal grew, and the artworks returned to Germany in 1949.

…no historical grievance will rankle so long, or be the cause of so much justified bitterness, as the removal, for any reason, of a part of the heritage of any nation, even if that heritage may be interpreted as a prize of war.

The Wiesbaden Manifesto, November 7, 1945. Quoted in Edsel, Robert M. Rescuing Da Vinci. Dallas: Laurel Publishing, LLC, 2006. P. 227.

After her time in Europe, Standen returned to the United States, this time to New York City, and sought of a museum career. Since she had little in the way of formal art history training, her original plan was to study at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts. However, her Sachs, Widener, and MFAA connections proved quite effective when Metropolitan Museum of Art director Henry Francis Taylor spontaneously offered her a job in the Met’s textiles department. Much more interested in paintings and sculpture, she initially hesitated, telling Taylor that she knew nothing about textiles, wasn’t interested in fashion, and didn’t like to sew. However, she still accepted the job, which she began on July 1, 1949. Standen stayed at the Met in one capacity or another until her death.

Just like when she worked for the Widener Collection, Standen proved herself to be a quick study, capable of effectively self-educating on the job. In a 1994 interview, she recalled spending late nights going through the collection piece-by-piece to learn everything she could. And it worked, as Standen eventually became a true expert and prolific writer in the field. The Thomas J. Watson Library online catalog lists 57 Met publications in her name. Standen served as an associate curator of textiles from 1949-1970. One of her main responsibilities was the Textile Study Room, where anybody who was interested could come in and see examples of the Met’s textiles collection up close.

Standen officially retired from the Met in 1970, but she continued to work there as a writer and consultant. It was as a consultant that she wrote perhaps her most significant work, the two-volume 1985 catalogue European Post-Medieval Tapestries and Related Hangings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Until her death in 1998, she continued to visit the Met’s Watson Library every day, conducting her research into the field that she initially had such little interest in, but which she eventually embraced so wholeheartedly.

Edith Standen doesn’t get as much attention as Rose Valland or many male Monuments officers. That’s probably because her story doesn’t have the life-or-death elements that theirs do. However, her actions protesting the American removal of art from Germany were heroic in their own way, showing a strong sense of morality and the courage to stand up for her beliefs in the face of greater authority.

It is not enough to be virtuous, we must also appear to be so.

Capt. Edith A. Standen. Quoted in Robert Edsel, The Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves, and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History. New York, Boston, and London: Back Bay Books, 2009. P. 422.

Her work in the immediate aftermath of World War Two, noteworthy though it certainly was, is only one facet of her long and successful career. I am struck by her resourcefulness and versatility, and I admire her ability to repeatedly self-educate and become expert in fields she had no formal training in. In the transcript of a lengthy 1994 oral history interview for the Met, Standen came across as savvy (even at nearly 90 years old) and forthright, but also humble about her many accomplishments.

I became interested in learning about Edith Standen after seeing her mentioned in the exhibition catalog Making the Met, 1870-2020. I hadn’t written about the Monuments Men in several years, but after researching Standen for this article, I realized that my timing in returning to this topic is quite appropriate. The story of the MFAA is one about the art world coming together to survive in almost impossible circumstances. And it reminds me a lot of what’s happening in the art world today amidst worldwide quarantine. Despite global shutdown, museums, galleries, and art historians everywhere are doing tremendous work in continuing to bring art to the world. The threat is very different, but the resourcefulness, determination, and passion is much the same.

Sources

- “Edith A. Standen: A ‘Monuments Man’ in Germany 1945-1947“. The Text Message. National Archives, January 2, 2014.

- “Edith A. Standen (1905-1998)“. Monuments Men Foundation For the Preservation of Art.

- Dobrzynski, Judith H. “Edith Appleton Standen, 93, Tapestry Expert“. The New York Times. July 25, 1998. Second D, page 16. Accessed online.

- Edsel, Robert M. Rescuing Da Vinci. Dallas: Laurel Publishing, LLC, 2006.

- McWhinnie, Bryce. “Defiant in the Defense of Art“. Prologue. Washington D.C.: National Archives, Summer 2015. P. 24-34. Accessed online.

- Sorensen, Lee, ed. “Standen, Edith.” Dictionary of Art Historians. 15 Apr 2020.

- Standen, Edith A. & Sharon Zane. “Interview with Edith A. Standen, January 6-13, 1994“. Transcript of an interview for The Metropolitan Museum of Art Oral History Project. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994.