I have recently gained a new appreciation for medieval enamels! Enamelwork consists of colored glass set in metal frames to create images or patterns. The effect is colorful, shiny, and wonderful, and here is some of what I’ve learned about the art form.

There are two different enameling techniques – cloisonné and champlevé. Cloisonné uses gold to build little partitions, creating cells into which different colors of powered glass are poured, then fired. It was popular in the Byzantine Empire and was also used in early medieval works such as the Sutton Hoo treasures. Champlevé utilizes copper, which is hammered down to create depressions to hold the enamel instead. It is usually gilded after the fact. Champlevé was popular in Romanesque and Gothic-era England and Europe, most notably in the enamel-working center of Limoges, France.

There were different regional schools of medieval enameling and two different aesthetics for enamel work. Either the figures can be enameled onto a metal background, or the figures can be left in reserved metal on an enameled background. Either way, I love all the different effects that go along with them, like the ways in which enamel colors were mixed within the same field, or the engraved details in the metal areas. Some objects also added additional pieces of cast metal to build up three-dimensional figures.

Enamels are easy to enjoy, no matter one’s art historical skill level. Some background information may help in understanding the specifics of the iconographies, but none is necessary to appreciate their aesthetic appeal. Their generally petite sizes make them easy to look at closely without getting overwhelmed. As square plaques, personal reliquaries, or other small-scale religious items, they come in lots of different shapes but remain primarily diminutive. Finally, they are common enough that plenty survive in museums all over the world. The immediacy that’s such a big part of their appeal is further enhanced by their unfading colors, dominated by lovely blues and greens.

Even in its time, enamelwork was a popularly accessibly art form, not just an elite one. Much like our modern-day earrings of colored glass, enamels gave the appearance of precious gemstones at a more affordable price. They came in different levels of quality and were sold to a proto-tourist market on the medieval pilgrimage route that passed through Limoges. While most people would turn up their noses at the idea of anything sold to tourists today being considered fine art, we are perfectly willing to respect and treasure medieval enamels that were made for a similar purpose. It seems that age changes our ideas about worthiness and lends its own cache.

Of course, not all enamels were mass-market items. They also appeared on lots of expensive, high-status, bespoke religious items, such as important reliquaries and altarpieces. Few examples survive intact today, but those that do are simply stunning! In most cases, however, such large-scale objects have been broken up, and the individual enamel plaques that decorated them have been dispersed to various museums and collections.

These objects remind me of something I once heard about how people who love medieval art also tend to love modern art, and vice versa, because the aesthetics are similar. I definitely see evidence for that here in enamels’ bright colors, simplified forms. These enamels remind me of Post Impressionism, or maybe even Pop Art, in their bold, clearly-defined, legible aesthetics. They remind me a bit of cartooning, as well.

I find it interesting that my favorite aspects of medieval art are diametrically opposed – monumental and monochrome (at least as they appear today) church architecture versus small, brilliantly-colored works like enamels and manuscript illuminations. In centuries past, some art theorists believed that people who were attracted to art with bright and shiny colors were simple-minded. According to them, the truly sophisticated people appreciated line, classical references, and all that nonsense instead. If that’s the case, I will gladly sign up for Team Simpletons. There’s something fascinating and joyful about these tiny treasures, and I’m a big fan.

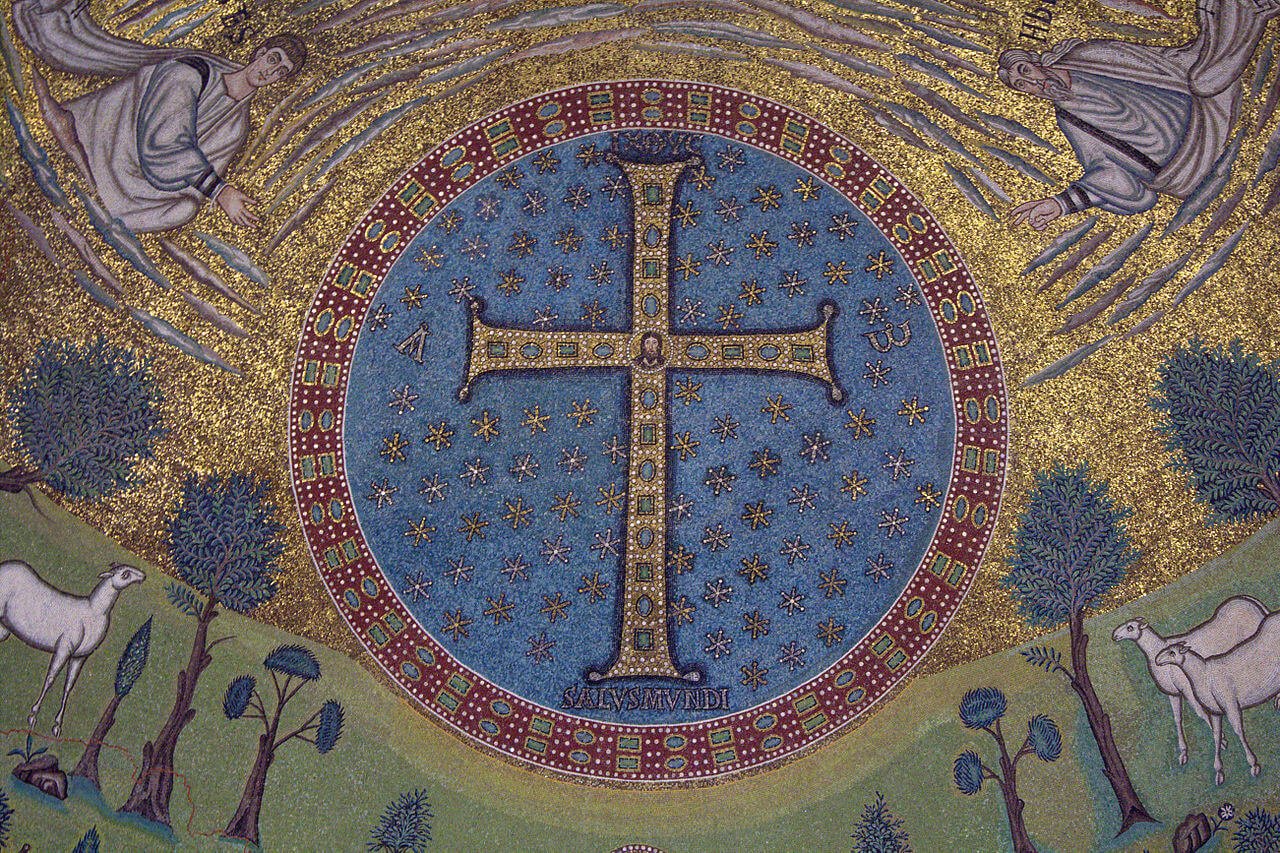

Bonus: I’ve also become hooked on medieval mosaics in recent months. Check out what I wrote about them below.

“All that Glitters: The Sparkling World of Medieval Mosaics“. Published on DailyArt Magazine, May 10, 2021.