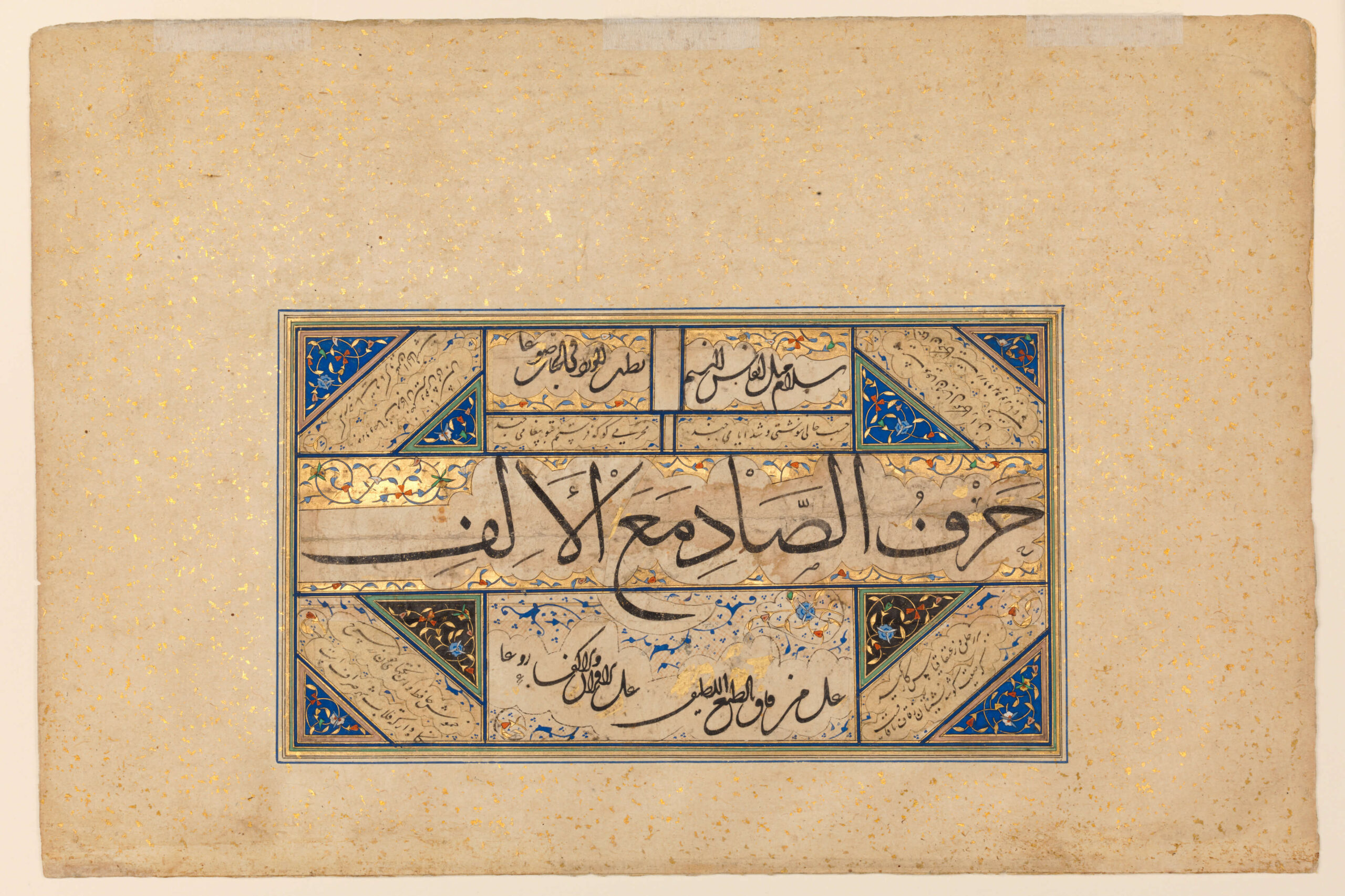

Cover image: Sultan Muhammad Nur, Page of Calligraphy, Iranian, early 16th century CE. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

This guide will introduce you to Islamic art. Unlike my other art and architecture guides, which cover artistic styles and movements, specific time periods, and geographic locations, this one discusses a much broader and more diverse category. Therefore, consider this post an introduction to what you’ll see in the Islamic galleries of an art museum rather than a definitive guide to a set of singular characteristics.

What is Islamic art?

The term Islamic art generally refers to artworks made in the so-called Islamic lands – those where the Islamic religion is or has been prominent. They are often ruled by Islamic leaders like sultans and caliphs. The area varies by historical period but can include:

- The Middle East

- Africa, especially North Africa

- Turkey

- Central Asia

- China

- India and Pakistan

- medieval Spain and Sicily

The artworks can date anywhere from the beginning of Islam in the 7th century CE to the present day. (Islam uses a different system of years than we’re used to, so you may see two different sets of dates next to an object.) Where contemporary art is concerned, Islamic art can be made anywhere in the world by people who practice Islam. There’s also a rich tradition of European artists actively emulating Islamic forms and motifs, but that’s not really considered Islamic art. And art from many of these geographic areas can fall under other headings as well.

Based on this definition, Islamic artworks are not necessarily religious in nature; they can equally be secular and often came from luxurious royal courts. Thus Islamic art may be tied closely to the Islamic faith or may simply have existed in proximity to it. Plus, these lands have historically been diverse places, so not all Islamic-style artworks were made by or for people who actually practiced Islam, and multiple diverse artistic traditions could have flourished in the same area at the same time.

As you can perhaps tell, what counts as Islamic art is actually pretty vague, so this label doesn’t really tell us much. For this reason, many people have argued for retiring the term altogether. Since it’s still commonly used, though, I think it’s worth understanding.

Multiplicity

Islamic art is not just one thing. Considering how much geography and chronology the term covers, it makes no sense to expect uniform characteristics throughout. That would be as unrealistic as expecting Christian art to remain consistent between medieval France and 19th-century Mexico. Local and native artistic traditions, regional differences, cultural exchange (especially with China, Venice, and Byzantium), technical innovations, and artistic development over time all mean that many different styles and traditions exist within the umbrella of the term Islamic art.

That said, some common elements do tend to appear throughout the arts of the Islamic world, and we’ll discuss them here. I will focus on historical art, but you’ll likely recognize many of these styles and traditions influencing Islamic art today.

Art Forms

These are some of the most prized art forms and those you’ll commonly see in the Islamic galleries. It is by no means a comprehensive list.

- Calligraphy is one of the most important art forms across the Islamic world, even today. Written in a variety of Arabic scripts (think of a script like a handwritten font), this calligraphy can spell out dedications, prayers, sayings, and more. Calligraphy isn’t limited to pen on paper. It can adorn all sorts of objects, from glass, ceramics, and metalwork to entire buildings. No matter the medium, it’s not solely the meaning that’s important but also the beauty, to the point that aesthetics can often supersede legibility. When the text is from the Qur’an, the simple fact of its presence is considered highly significant. Click here to see a modern-day Islamic calligrapher explain her venerable craft.

- When we talk about painting in Islamic art, we’re usually referring to manuscript illumination, another prized art form throughout Islamic history. Obviously, religious manuscripts, most notably the Qur’an, are the most important. They tend not to use lots of decoration, placing all the emphasis on the elegant calligraphy of the text as well as things like harmonious page design and dazzling gold leaf. By contrast, secular manuscripts, especially poetry and other literary works, often include elaborate illustrations. Standalone paintings or drawings on paper, which look a lot like manuscript illuminations, also appear, but large-scale easel painting has not been a major part of the Islamic art tradition.

- Ceramics is another art form popular throughout the Islamic lands. This includes three dimensional wares like bowls and jugs, as well as tiles. It’s particularly in ceramics that we see the influence of China, from the blue-and-white color scheme to the cloud scroll motif. Although the brilliant blues and shining lustrewares are the most eye-catching, ceramics in the Islamic world had many different techniques and styles. Glass and metalwork are also prevalent luxury art forms, tending to share forms and motifs with ceramics.

- Colorful ceramic tiles are a major form of architectural decoration in the Islamic world in both sacred and high-end secular buildings. These tiles can be rectangular or have more complex, interlocking geometric shapes like stars or hexagons, or they may depict scenes and motifs that play out over multiple tiles. Some of the world’s most famous tiles came from Iznik in Turkey.

- Persian (Iranian) carpets are the most famous in the world, and Islamic textiles of all sorts were once highly coveted and exported all over the world.

- Although the architecture of the Islamic world is beyond the scope of this post, it’s common to see furnishings and architectural fragments in museums. For example, mihrabs are the arched niches within mosques that mark the direction of Mecca. They are heavily decorated, often with particularly spectacular tiles. Minbars are staircase pulpits and are often made of intricately carved and inlaid wood or stone. Muquarnas is a type of ceiling decoration made up of interlocking, honeycomb-like niches. Mosque lamps – urn-shaped glass or ceramic light fixtures that hang from mosque ceilings – are among my personal favorites.

Subject Matter

You’ve probably heard that Islamic art doesn’t include any figurative imagery (people and animals) because Islamic law forbids it. This is only partly correct. It’s definitely true that Islamic art uses figurative imagery rather cautiously, and its appearance could prove controversial. (This is why you’ll sometimes see that faces have been obliterated from said scenes.) However, the specifics of what was and wasn’t considered acceptable vary according to time and place. It’s uncommon, but not unheard of, to find human and animal imagery in religious art and architecture. On the other hand, you’ll find plenty of people and animals depicted in non-religious art. Subject matter includes real and fantastical creatures, science, history and myth, war, scenes of luxurious life at the royal courts, and elite pastimes like polo, music, and chess.

Even when it does appear, however, figurative imagery is definitely not the most significant subject matter in Islamic art. Instead, that position goes to abstract or semi-abstract patterning, especially calligraphy, complex geometric designs, and plant motifs. These motifs, often in combination with one another, may easily cover an entire object, whether a candlestick, a textile, or a suite of tiles. Think of them as the visual main event, not background or filler. You might have to look closely, but you’ll likely find Arabic calligraphy on the majority of objects. To those of us who aren’t familiar with this language or writing system, it can be easy to overlook it amidst the profusion of other decoration.

Just like in basically every other artistic tradition on earth, you’ll see many different styles of depicting these motifs, whether figurative or abstract, across the breadth of Islamic art Just because these subjects recur doesn’t mean they look the same every time or that they have the same significance everywhere they appear. However, it’s pretty safe to say that the naturalism so prized in the Christian west does not generally play a big role in Islamic art.

Where to See It

The following are some of the best museums to see Islamic art. I have not visited them all personally. Let me know if you have a favorite I’ve missed.

- Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

- Victoria and Albert Museum in London

- Museum of Islamic Art in Doha

- Museum fur Islamische Kunst in Berlin

- Topkapi Palace Museum in Istanbul

Resources

- Ekhtiar, Maryam D., Priscilla P. Soucek, Sheila R. Canby, and Navina Najat Haidar eds. Masterpieces from the Department of Islamic Art in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011. This book came out when the Met opened its new Islamic Art galleries and gives a great overview of the collection.

- Ekhtiar, Maryam D. and Claire Moore eds. Art of the Islamic World: A Resource for Educators. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed September 5, 2023.