It’s back to school time, and a whole crop of new students are starting the semester with introductory art history. I miss sitting in darkened lecture halls, looking at beautiful things projected on the screen, and learning about their fascinating histories. (I’m not sure I miss studying for the exams, though.) Studying art history in college is a very rewarding experience, but it can initially be a bit confusing, especially for brand new freshmen. Exam time can be stressful for students of any level.

Here is my best advice about what to expect, how to succeed, and how to prepare for exams. I hope it will help anyone taking art history in college, whether you’re an art history major/minor or are taking your first-ever art history class. (Want to know why you should study art history? I’ll give you seven reasons here.)

Note: My advice is based on my own college experiences, and things might be done differently elsewhere, particularly in schools outside the United States. If your experience has been different than what I describe, I would love to hear from you so that I can expand on this article.

Types of Art History Classes

If you are taking art history for the first time, changes are good that you’re taking a survey course. The time-honored introduction to the subject, survey courses cover a wide variety of subject matter, focusing on the broad characteristics of artistic and architectural styles in historical progression. Traditionally, the art history survey is two semesters which together cover the history of western (mainly western European) art from prehistory to the present day. You don’t have to take both semesters unless required for your major. In recent years, some schools have reworked their surveys to include material from non-western cultures. These courses are lecture based and teach a set of artworks your professor has chosen because they illustrate important concepts or epitomize key attributes of their style or movement. These classes also include reading assignments (often from a survey textbook like Janson’s History of Art, the Western Tradition), tests, essays, and possibly a museum trip if logistics allow for it.

The next level up is the slightly more advanced class that focuses on more specific areas of art history. Art history students usually have to take a selection of these in different areas (pick one ancient course, one Medieval or Renaissance course, etc.), but non-major/minors are usually also welcome. Like the survey, this type of class includes a strong lecture component focused on understanding the topic through specific artworks that students are tested on. However, it is balanced with a greater emphasis on learning art historical skills through more sophisticated reading and writing assignments, class discussions, and presentations. The most advanced classes, typically only open to art history majors and minors, are the classes completely focused on research, writing, and art historical methodology. I did not have to take any exams when I took these upper-level classes, but that may not be universal.

Art History Exams: What to Expect

Art history exams typically include an object identification section along with one or more essay prompts of varying lengths. In my experience, things like multiple choice and fill-in-the-blank questions, which are pretty typical in other subjects, aren’t common in college art history. They may appear, but they won’t be the core of the exam. The AP Art History exam (given in some American high schools), however, does have a hefty multiple choice section.

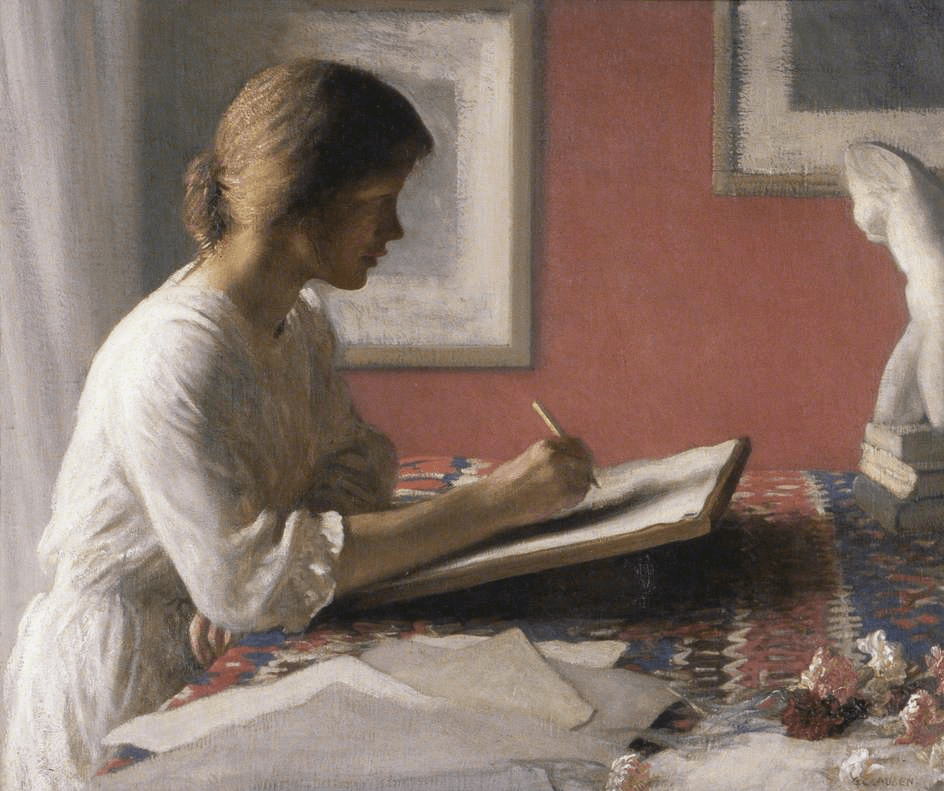

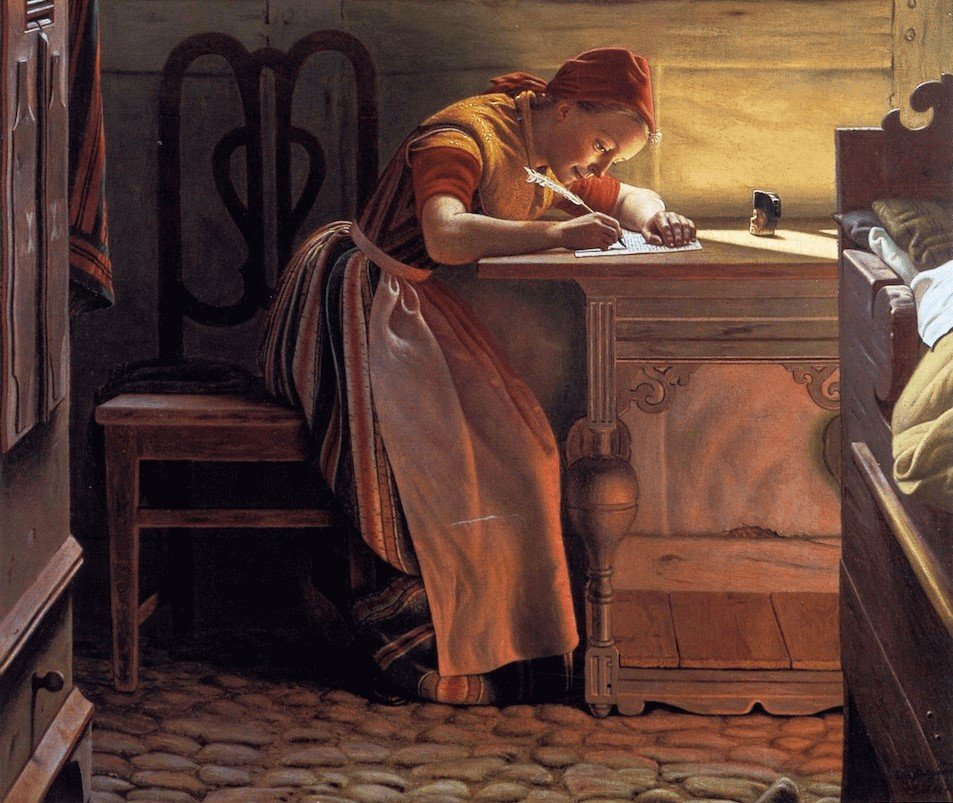

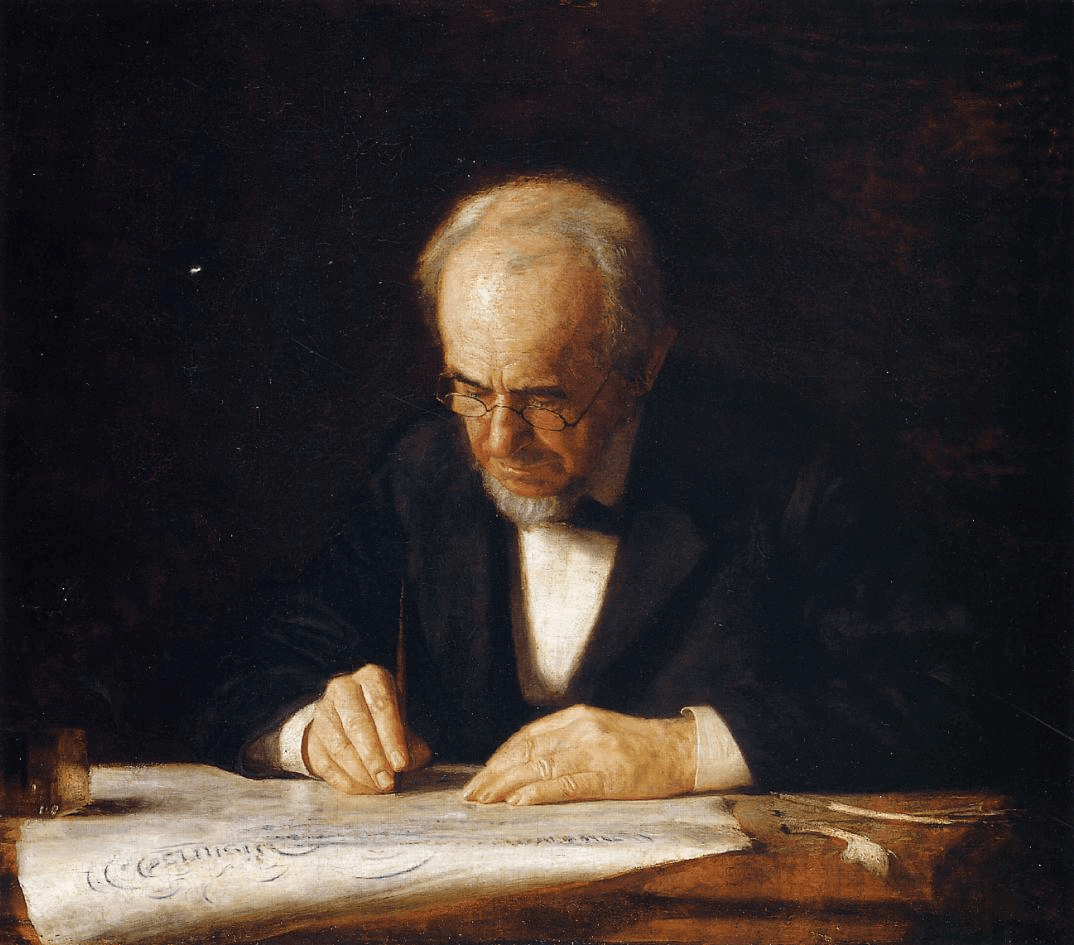

Object Identification

Object identification doesn’t really have a parallel in any other subject I can think of, it requires extra explanation. In this section of the exam – it’s usually up first – you’ll be shown a series of images without captions, and you will have to correctly identify the works of art depicted. Provide the title of the work, artist’s name, date of creation, and other information like the materials or where it was made. Most professors will also make you write a few sentences about the work’s importance and interpretation. Check with your professor to find out exactly what you’ll be required to include, but you’ll probably want to put down any relevant information you can possibly recollect. Don’t worry! You will only have to identify artworks that you have already met in the class.

Essays

In the essay section, you will have to write multiple essays of different varieties. One common type is the comparison essay, where you’re given two artworks to identify, compare, and contrast. Like object identification, this is a question type not found in most other subjects. The objects juxtaposed in the comparisons usually point towards lager ideas you’ve learned, so you’ll want to discuss the reasons for and significance of these similarities and differences in order to get maximum points.

Another essay type, which is usually longer and worth more points, involves a written prompts relating to broader themes from the course as a whole.

How to Prepare

When studying for an art history exam, you have a few goals:

- To be able to properly identify any work of art or architecture that might appear on the exam.

- To be able to explain each work’s interpretation and significance.

- To understand and express the major ideas that tie objects together.

But before all that, take good notes!

I hope you’re reading this early enough in the semester to apply this first tip. It’s really important to take good notes in your art history lectures so you don’t have to rely on your textbook alone for study material. This is also true in every other academic subject, but art history is a particularly subjective discipline where quite a lot of information – even fairly basic information – can subtly vary from source to source. That’s why you want to keep a good record of exactly what your professor said, taught you, and emphasized. Your textbook may provide a slightly different focus in some areas, and while one isn’t more valid than the other, your exam is most likely to reflect the viewpoint of the professor who wrote and graded it. For example, if your professor is particularly keen to discuss historical context and does so in more depth than the textbook, she will likely mention extra information in that area that she will expect you to know for the test.

Practice Identifying Objects

Identification is key, because it’s very difficult to write about something when you have no idea what it is.

All professors do object identification a little differently, so you’ll want to find out which artworks can potentially appear on the exam. Some professors only include works that they have specifically lectured about in class. Others consider anything that has come up in any of the required readings – those endless textbook pages you’re assigned each week – to also be fair game. In my experience, professors aren’t trying to make your life difficult here, and they tend to be forthcoming about what they expect. Most will even provide pdfs of their lecture presentations to study from.

I suggest making flash cards to help you study object identification. This is easy if your teacher gave you presentations you can print out. If you study from the textbook, the surrounding content will give you hints that you won’t get in the actual exam. Practice writing down the information instead of just reciting it back to yourself, since you’ll need to be able to spell lots of names from all different languages. Here are a few other things to keep in mind while you study for this section:

- Be prepared to identify architecture from multiple points of view, since the photo shown in your course materials won’t necessarily be the same one that appears on your exam. Study both interior and exterior views.

- If your course materials include ground plans of buildings, study those as well. You may be asked to identify a building through its ground plan. (Art history professors just love to do that, particularly when church architecture is involved.) I have definitely heard gasps of horror when ground plans have appeared on exams, since many students don’t study them. Learn from their mistake.

- It’s common for dates, spellings, and even the titles of works to differ from source to source. Unless you’re told otherwise, go with the information your professor has used in lectures and handouts, then fill in any gaps using what’s in your official course textbook (not Wikipedia!). Generally, you’ll be allowed a greater margin of error with ancient art, where dates are approximate ranges and titles are often unofficial.

It’s a horrible feeling when you get an object to identify and realize you have absolutely no idea what it is. Do yourself a favor and at least familiarize yourself with every object and image that could possibly come up.

Studying Significance, Interpretation, and Broad Ideas

Beyond simply knowing all the names and dates, make sure you really understand the significance of each artwork you study. There are millions of artworks in the world, but only a few can fit into any semester of art history. Your professor had to carefully decide which objects to include in her* syllabus. Think about why each object made that cut. It’s not always a case of superlatives. Sometimes an artwork might be the first, biggest, most famous, etc. More often, though, an artwork is included because it’s a great example of a particular idea, such as a technique that was popular at the time or a key step in a style’s development. Looking for each artwork’s importance in this way will help you pick up on all the key concepts. It’s also much more fulfilling than just memorizing things by rote. If you know what’s noteworthy about each object, discussing and comparing them will be pretty easy.

To prepare for the broader essay questions, go back through your readings and class notes to identify the main ideas. What topics come up over and over again? Which objects and artists did the professor spent a long time talking about, and what did she indicate was so important about them? If you pay attention, the professor always lets you know what the big ideas are. I’ve never once seen an essay prompt on an art history exam and been surprised by it. I’ve almost always thought “of course she’s asking this”. Even if I wouldn’t have necessarily predicted the prompt ahead of time, its appearance always made sense to me because it reflected an area the professor had given a lot of focus in her lectures.

Keep in mind that art history classes aren’t exclusively about the individual objects; they’re at least as much about the broader history of artistic production and development over time. So, look for the themes that tie things together. Try to see how objects connect to each other, like how a few different objects show a style developing over time or a similar theme treated differently by different cultures according to their values. Think about why certain works look the way they do. Pay attention to historical context whenever it’s mentioned, and look for how that context is reflected in the art.

With all of that being said, don’t let this focus on the big picture stop you from studying the smaller stuff. I suggest spending a least a little time on every piece of content that has come up in the lectures, even if it wasn’t prominent. You never know what detail will get you an extra point or two.

Writing Tips For Art History Exams

My professors always used to tell me to write about what I know, not what I see. That means going beyond simply describing the artwork to discuss the ideas behind it. Anyone who looks closely can write a decent object description, even if she hasn’t been paying attention in class. Discussing the facts that you’ve been taught is what shows that you know the material. Your professor wants to know that you’ve been listening to her lectures, not simply looking really closely on the pictures on the screen. You obviously need to reference the visual, because that’s what makes it art history, but you won’t get any points for just describing a work without going further. Don’t write “Object A is small, while Object B is large”; say something like “Object A is small because it was a devotional object made for personal use, while Object B is a large-scale work because it had to fill a large church space and be visible to the entire congregation.”

Know your vocabulary. I once lost a ridiculous number of points on an exam for failing to mention one relevant vocabulary word. This isn’t the norm in my experience, but it’s definitely a good idea to make sure that you are familiar with all the vocabulary words you’ve learned in class and which works they apply to. Use these words into your writing to show that you understand them – as long as you feel confident that you’re using them correctly.

Finally, and I cannot stress enough how important this is… always begin your essays, particularly comparisons, by thoroughly identifying any artworks involved, just like you would in an object identification question. The classic way to do this is to start an essay by saying “The object on the left is [identification goes here], and the object on the right is [identification goes here]” before moving on to your main points. Professors will take off a lot of points for lack of a proper identification. Don’t write a great essay but get a bad grade because you never mentioned the title of the artwork you were discussing.

Other Writing Assignments

In addition to your exams, expect to write one or more essays throughout the semester, including a research paper. How many such assignments you’re given, the word or page count, and the difficulty of the topics depends on the level of the class. In any case, you will usually get to choose from a few possible topics or at least be able to choose which artwork(s) you want to write about. Unlike exam essays, these assignments are less likely to test your understanding than they are to help you develop skills like visual and historical analysis or the ability to form and defend an interpretation based on visual evidence. The higher level the course, the stronger the research component. A survey course may not include a research paper at all, while an upper-level course will likely have research as its main event.

Good luck with your art history classes, exams, and papers! I hope that my advice has helped you and that you enjoy your art history adventure overall. If you want to share your own experiences or need some guidance, please leave me a comment below. I love to hear from art history students and will help you in any way I can.

*The hypothetical art history professor in this article is always female because all my college art history professors were female. A million thanks to Rita, Peggy, and Kim for teaching me, encouraging me, nurturing my love of art history, putting up with my more excessive tendencies, and occasionally frustrating the heck out of me!

Not a college student but still want to learn art history? Get my book The Art Museum Insider and learn the basics of art history thinking skills.