Eve Kahn’s new book Forever Seeing New Beauties: The Forgotten Impressionist Mary Rogers Williams, 1857-1907 (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2019) tells the life story of Connecticut-born painter Mary Rogers Williams (1857-1907). Defying the societal contentions of her time, Williams dedicated her life to painting, teaching at Smith College, and travelling widely throughout Europe. She achieved modest acclaim that faded soon after her early death, but she escaped total oblivion thanks to the dedication of her longtime friend Henry C. White. Based on years of research and boxes of old letters, Forever Seeing New Beauties tells her story for the first time ever.

Eve Kahn is an independent historian, which means that she’s not attached to any museum or other institution and is free to take on projects of her choosing. She contributes to some impressive periodicals, including The New York Times, Antiques, and Apollo. She has been drawn to writing about history since childhood and loves to explore nearly-forgotten stories where “there’s a wisp of something and nobody knows if anything survives”. Last week, Kahn was kind enough to sit down with me to talk about her book, her research, and the important work of “resurrecting” forgotten female artists.

What were your expectations and motivations when you first started researching Mary Rogers Williams?

Kahn first became interested in Mary Rogers Williams through a painting owned by her art historian mother. (Ironically, she later discovered that the painting was actually by another artist.) She says she was initially just curious and wanted to be able to tell her mother something about the artist’s life and work. She has done similar research on other paintings before. She never expected to find so much information, and she definitely never expected to write a book about it.

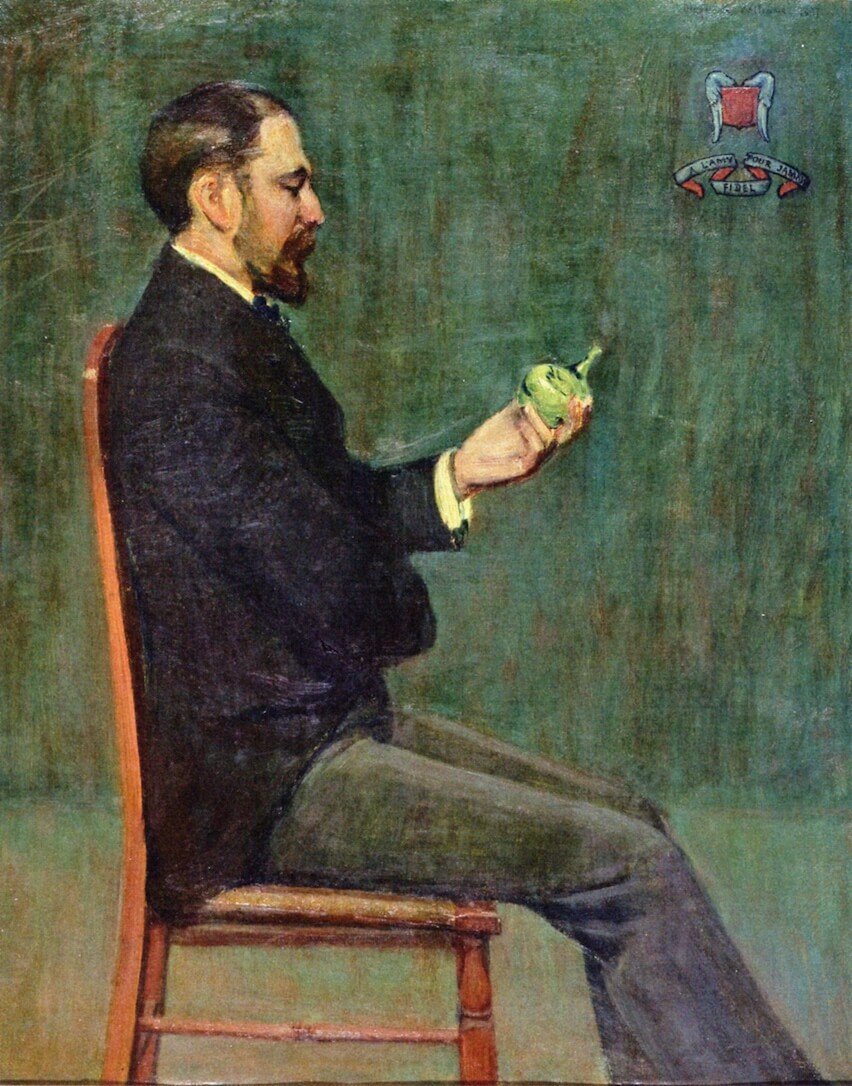

The trail quickly led her to the descendants of Williams’s close friend and fellow artist Henry C. White (1861-1952). White came into possession of Williams’s paintings, letters, and other papers after her death, and his family has preserved them in its Connecticut boathouse for over one hundred years. Henry White’s grandson Beeb was more than happy to show Kahn everything when she first visited him in 2012. Kahn was shocked by how much survived. She soon began transcribing Mary’s letters.

When did you decide to write the book?

People had been asking Kahn for years when she was going to write a book, but the idea had never appealed to her. She used to say that she would only write a book if some fabulous and previously-unpublished archive were to suddenly appear and essentially demand her to. And that’s exactly what happened!

The White family has a longtime connection to the Florence Griswold Museum in Old Lyme, Connecticut. Henry and his son Nelson both spent time at Miss Florence’s boarding house, where both contributed panels to her famous dining room. The Whites reached out to the museum, which eventually held Mary Rogers Williams’s first-ever museum retrospective in 2014-15. Griswold curator Amy Kurtz Lansing contacted Wesleyan University Press, and suddenly, Kahn found herself presenting her research to her future publishers.

Tell me about your research process in a case like this, when you have to break totally new ground because there’s no prior literature.

Kahn spent about seven years researching Williams. She pored over the New York Public Library’s newspaper databases to find contemporary reviews of Mary’s work, as well as a few more recent mentions. She also searched exhibition catalogues from places she knew Mary had shown work, such as the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. When digital resources failed her – fewer were available seven years ago than today – she visited institutions in person. These included the Connecticut Historical Society, Yale University, Smith College (her most frequent destination, because of Mary’s long employment there), Historic Northampton, and the Archives of American Art. New material continued to surface right up until the book’s publication and even beyond. Recently, someone brought a stack of Mary-related letters to Kahn at her lecture in Boston.

Kahn emphasizes that it is a miracle for Mary Rogers Williams’s legacy to survive intact. Many other women haven’t been so lucky. The vast majority of pre-20th century female artists remained unmarried, since marriage and a career were long considered incompatible. No husband, and thus no children, meant that these women left behind no direct descendants with an interest in preserving their artistic legacies. As a result, many female artists’ works have been thrown in the garbage by uninterested in-laws. Mary was lucky to find such strong advocates in the White family. Kahn describes the Whites as “delightful”, enthusiastic, and completely unembarrassed of anything that could possibly emerge from the Williams archive. That’s a rarity, since Kahn has seen too many cases where men have tried to twist or even erase female artists’ stories posthumously. When I asked why it was important to tell Mary’s story, Kahn told me: “It’s important for anyone who feels their voice isn’t heard to know that their story is important, too.”

What other female artists have you discovered along the way?

While researching Mary, Kahn also looked into several other female artists, including Mary’s Smith colleagues Clara, Bessie, and Susanne Lathrop, and her roommate Julia Dwight. And she has an entire list of American women to explore next. Often, Kahn says, a little-known woman’s artwork appears for sale and just “grabs” her. In many cases, she has been thrilled to find living descendants who remember hearing stories from people who actually knew the artist.

How has the book’s reception been? Do you see more interest in Mary’s work now?

Forever Seeing New Beauties has gotten a great reception. Kahn has lectured about Mary Rogers Williams in New York, Connecticut, and Massachusetts. She says she’s having a lot of fun spreading the word. She was excited to give a talk in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s boardroom and find that the museum luminaries in attendance really loved the story. She and her book have also been the subject of several articles and interviews, including one in Vogue.

“It has been fun to be part of the Resurrectionists”, says Kahn. She’s referring to the growing group of people actively working to bring forgotten women back into the spotlight. She has observed increasing energy in this area recently, pointing to exhibitions like the record-breaking 2018 Hilma af Klint show at the Guggenheim as evidence that both audiences and major museums are now more interested in these subjects than ever before.

What advice do you have for people interested in learning more about female artists?

Kahn suggests asking questions. Any time you visit an art museum, historic house museum, or historic library, she says, ask about where women fit in. Try questions like “who made that” or “who paid for that (that we don’t know about)”. In recent years, museums have begun to tell stories about women, slaves, and other traditionally-overlooked parties because they know visitors want to learn about them. So, keep asking! Besides painting and sculpture, there’s a long history of skill and achievement in so-called “women’s work” – artforms like embroidery and quilting. Additionally, women were prominent artistic patrons much more often than they’re usually given credit for. Some played important roles in establishing museums and libraries, while others did critical work campaigning to save historic structures. Don’t expect immediate answers, institutions may be too understaffed and overworked to delve very deeply into this subject. However, you might discover a little nugget that you’ll decide to explore on your own.

Kahn laughingly said “let’s crowdsource!” when I first asked this question. I’m not sure if she was kidding, but that certainly sounds to me like a viable way of rediscovering forgotten female artists. Contact Eve (or me) if you have any tidbits you’d like to share.

Thank you so much to Eve Kahn for meeting with me, buying me a coffee, and having a lovely conversation with me. And thanks to Stuart Lutz for introducing us to each other. I highly recommend Eve’s book, Forever Seeing New Beauties: The Forgotten Impressionist Mary Rogers Williams, 1857-1907.