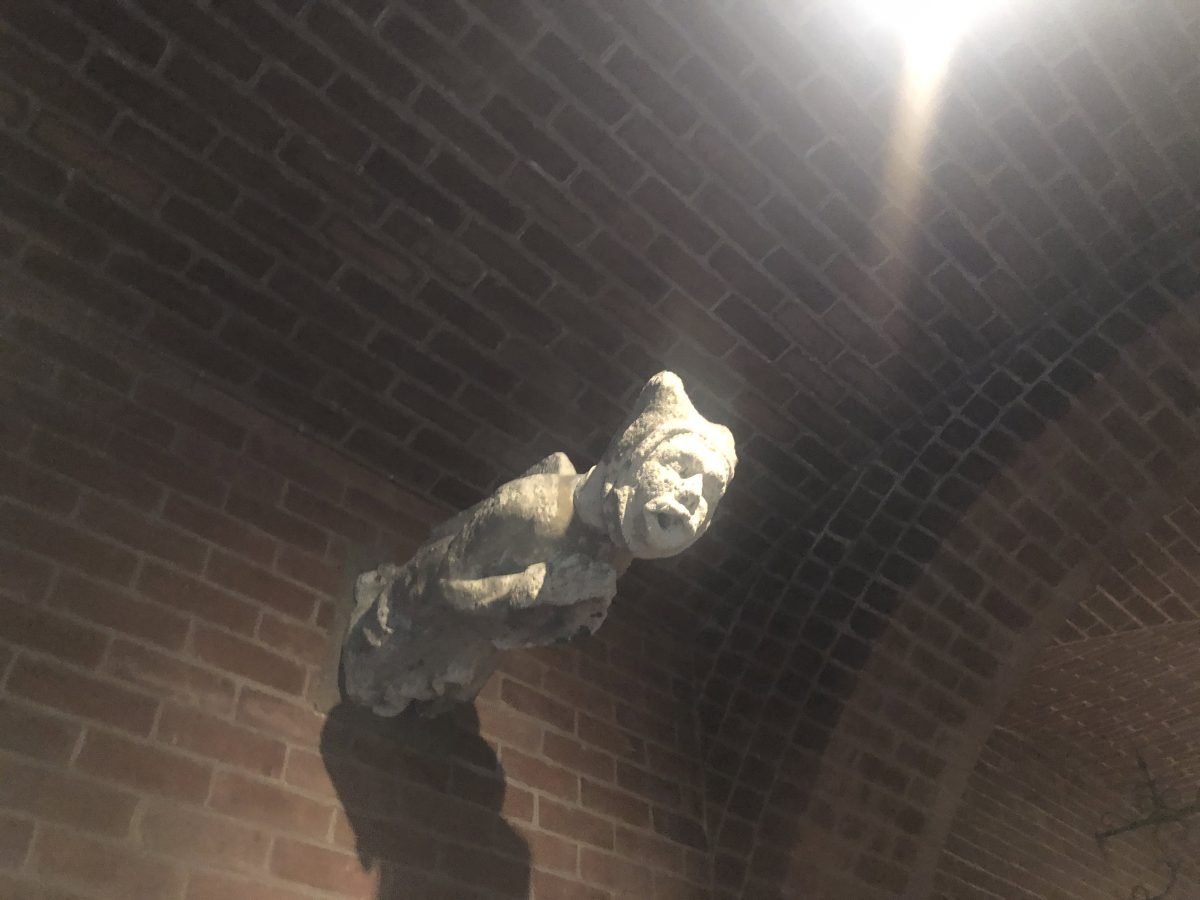

Cover image: This person-shaped gargoyle now lives indoors at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. Photo by A Scholarly Skater – all rights reserved.

I have started reading the first of the three gargoyle books I got from the library: Holy Terrors: Gargoyles on Medieval Buildings by Janetta Rebold Benton, an art history professor at Pace University. I have only read the introduction so far, but it was lengthy and contained lots of good material, so I thought I would share what I have found out so far. All citations are from: Benton, Janetta Rebold. Holy Terrors: Gargoyles on Medieval Buildings. New York: Abbeville Publishing Group, 1997.

- Gargoyles (specifically in their drain-pipe function) were used in ancient Egypt, Greece, and Italy (p.11).

- A charming legend has it that the original gargoyle was the remains of a dragon named “La Gargouille”, who terrorized a French town and was burnt at the stake by a priest (p.11-12).

- Some of the first known medieval European gargoyles are on Laon Cathedral in France and date to around 1220 CE (p.12).

- There is a recognizable evolution of gargoyle design in the Middle Ages, both in the complexity of the designs and in the characteristics of the creatures depicted (p.12-15). However, plain drain spouts were also used at all times in the Middle Ages (p.11).

- One of the ways you can spot a later gargoyle on a medieval building is by what type of animal it depicts. Some gargoyles represent animals that Europeans didn’t know about in the Middle Ages, so if you see one of these animals as a gargoyle, you know it isn’t medieval. The author mentions rhinos and hippos as two examples, but I’m sure there are more. Fortunately, there are a lot of surviving medieval bestiaries (books of beasts) that can provide some insight into who knew about what when (p.20).

- Gargoyles were probably originally painted and gilt (p.20). This one probably surprised me the most, but now that I think, it really shouldn’t have. In school, I remember learning about how Gothic churches used to be brilliantly painted, and I remember seeing photos of a church that was re-painted in what art historians thought would have been the original style, so the idea that the gargoyles would have also been painted should not have been big news to me. This blog post provides some insight into repainted Gothic and Gothic Revival churches. Some of them remind me of the church I was Confirmed in, which had been completely repainted shortly before that event. Unfortunately, I have no good photos of it; I may have to remedy that.

- Popular legend has it that the gargoyles of Notre Dame de Paris watch over the Seine River to make sure no one drowns (p.39).

- In addition to manuscripts, which Benton discusses, grotesque creatures were frequently featured on medieval misericords. Misericords were little benches used by the clergy in churches (p.40). Though I had heard of misericords before, this is the first time I have heard anything about them having grotesques on them. Needless to say, there will be a misericord post as soon as I have time to do the necessary research.

The rest of the introduction consisted of a very excellent summation of many theories behind the meaning of gargoyles, along with the pros and cons of each. I am eager to talk about this, but it will have to wait for tomorrow, because I am exhausted and have a busy day tomorrow. If you are hankering for more medieval architecture before then, visit the website of Alnwick Castle in Northumberland, Scotland. If it seems familiar, that is because Alnwick Castle played the role of Hogwarts in the first two Harry Potter movies.