Here in the United States, paintings play a big role in how we experience the story of our country’s origins. Portraits of our Founding Fathers and other paintings of the Revolutionary War appear on our money, in our textbooks, and decorating our government buildings. These paintings have become a huge part of our national consciousness, but most of us don’t often think about the paintings themselves.

Paul Staiti’s Of Arms and Artists: The American Revolution Through Painters’ Eyes (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2016) is about the five American painters most responsible for depicting the Revolution era – Charles Willson Peale, John Trumbull, Benjamin West, Gilbert Stuart, and John Singleton Copley. I was really surprised and intrigued by a lot of what I learned in the book.

First of all, the situation in which many of these paintings were created was pretty delicate. There wasn’t much of an American art world at the time, so any aspiring artist from the colonies had to spend time in London. As you can imagine, this posed some problems during the Revolution. John Trumbull, who once served in the Continental Army, was arrested in London as an American spy. Clearly, caution and diplomacy were needed. The situation was particularly difficult for Benjamin West. He had moved permanently to England before the war and had risen so far in the London art world that he was official painter to King George III himself. West supported American independence, but his position made it pretty much impossible for him to express his views or to paint anything obviously pro-America.

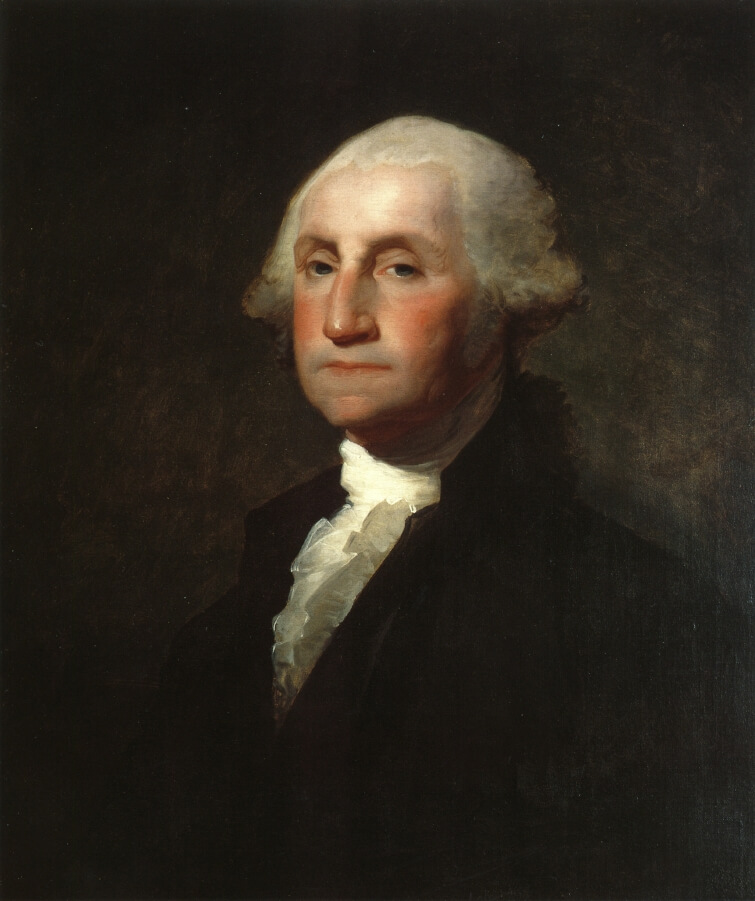

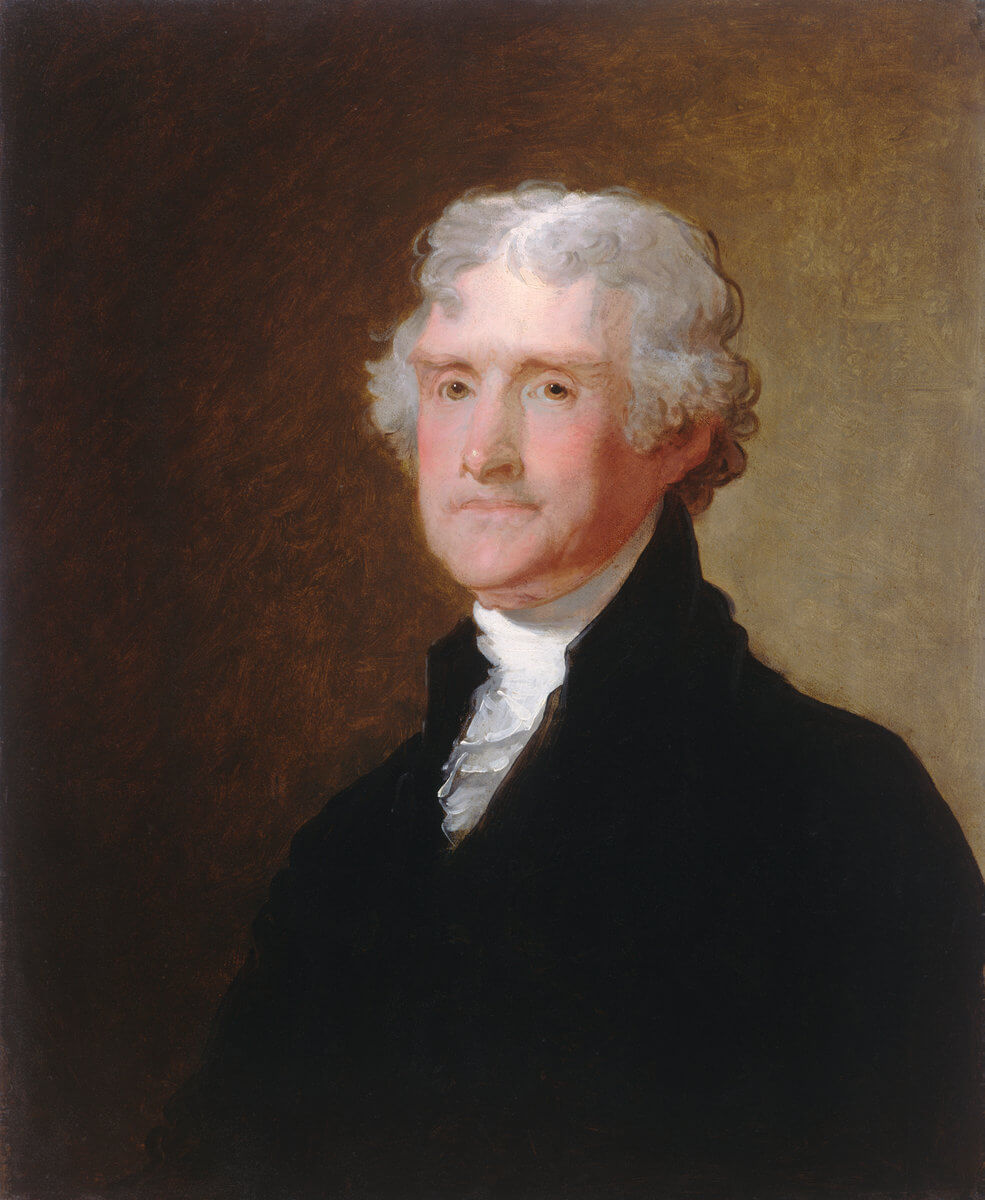

Even after the war was over and the British had moved on, it was still a difficult climate in which to paint pro-American works. That’s why most of the artists discussed in the book eventually moved back to the States to paint Revolutionary works. There was an eager market for portraits of George Washington, in particular, among the new country’s new citizens.

Unsurprisingly, portraiture and history painting were the two main genres that depicted the people and events of the American Revolution. At the time, allegory and classicizing references were very fashionable, particularly in history painting. Lots of American artists, and even some non-American artists, used classical and Biblical references in their paintings of Revolutionary scenes. For example, George Washington was often compared to a Roman general named Cincinnatus, who resigned his post and went back to his fields after the end of the war. Patriots who died in the struggle were shown to be like Christian martyrs or even sometimes like Jesus. In some cases, artists soften the potential controversy of painting scenes supporting the American Revolutionary by painting classical history paintings with underlying messages relevant to the war.

In general, history paintings often took huge liberties with the facts for the sake of drama and allegory. Those that depict the American Revolution are no different. John Trumbull’s famous series of events and battles of the Revolution, including five works that now hang in the U.S. Capitol Building, are full of inaccuracies. Some are pretty significant, like two events that actually happened miles and hours apart being shown occurring side-by-side. Trumbull definitely did this on purpose, since he fought in many of those battles and knew quite well how it actually went down.

Perhaps most surprising to me was learning that the artists whose works have given generations of Americans windows into the war for independence weren’t necessarily the steadfast patriots one might assume. Some of the artists, like Charles Willson Peale, were strong supporters of American independence. Others, not so much. John Singleton Copley’s family sided with the British, and Copley kept his own political views close to the vest. It seems that most of us know a lot more about the people shown on the canvases than the artists behind them.

These are just a significant few of the many things I learned in Staiti’s book about the American Revolution’s artists, paintings, key figures, and even about the Revolution itself. If you’re interested in American history, early American art, or the eighteenth century in general, I would highly recommend this book.