Irving Stone’s The Agony and the Ecstasy is a 1961 biographical novel about Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564). Several people have recommended this book to me, including one blog reader who asked for my thoughts on it. I’m glad that people kept pushing me towards this novel until I couldn’t resist anymore; I enjoyed it greatly and recommend it highly. The book is over 650 pages, but it’s pretty easy to read. Engaging and intelligent without being aggressively highbrow, it flows nicely and is organized into manageable sections.

The novel starts when thirteen-year-old Michelangelo becomes an apprentice to Florentine painter Domenico Ghirlandaio and continues through his death at age eighty-eight. Along the way, readers really get to know Michelangelo – or at least a version of him – see him grow and change, and get an idea of what made him tick. Stone did a spectacular job of fleshing out Michelangelo’s inner life, making him into somebody I could actually relate. As I worked my way through the book, this towering, near-mythic figure really starting coming to life for me. The book particularly shines when it explores the intention and emotion behind his artworks.

The Agony and the Ecstasy is a fascinating dichotomy in the sense that it reads like a fictional novel, except when it doesn’t. That’s because Stone got to interpret and portray the story of Michelangelo’s life, but he didn’t create the actual story itself. While I’m sure he elected to highlight certain events over others, I don’t get much sense of him manipulating the source material for dramatic effect. It was refreshing, in a way, to not be able to question how the “plot” unfolds. I’m no expert on Michelangelo, but I was aware of the major events and enjoyed sparks of recognition at key moments, like the creation of his great Pietà.

What I most enjoyed in The Agony and the Ecstasy was learning about Michelangelo’s relationships, from his complicated dynamic with his financially-dependent family to his lifelong friendships with fellow apprentices and his four great loves. It was so fascinating to watch him interact with Renaissance luminaries as his peers and contemporaries, particularly the Medici family. Michelangelo spent his teenage years living in Lorenzo de’ Medici’s palace and studying in his sculpture garden. Stone portrays Michelangelo’s relationships with Lorenzo and his family, including future Popes Leo X and Clement VII, as especially close. I found his long-lasting friendship with Lorenzo’s youngest daughter, Contessina, to be one of the most touching aspects of the story.

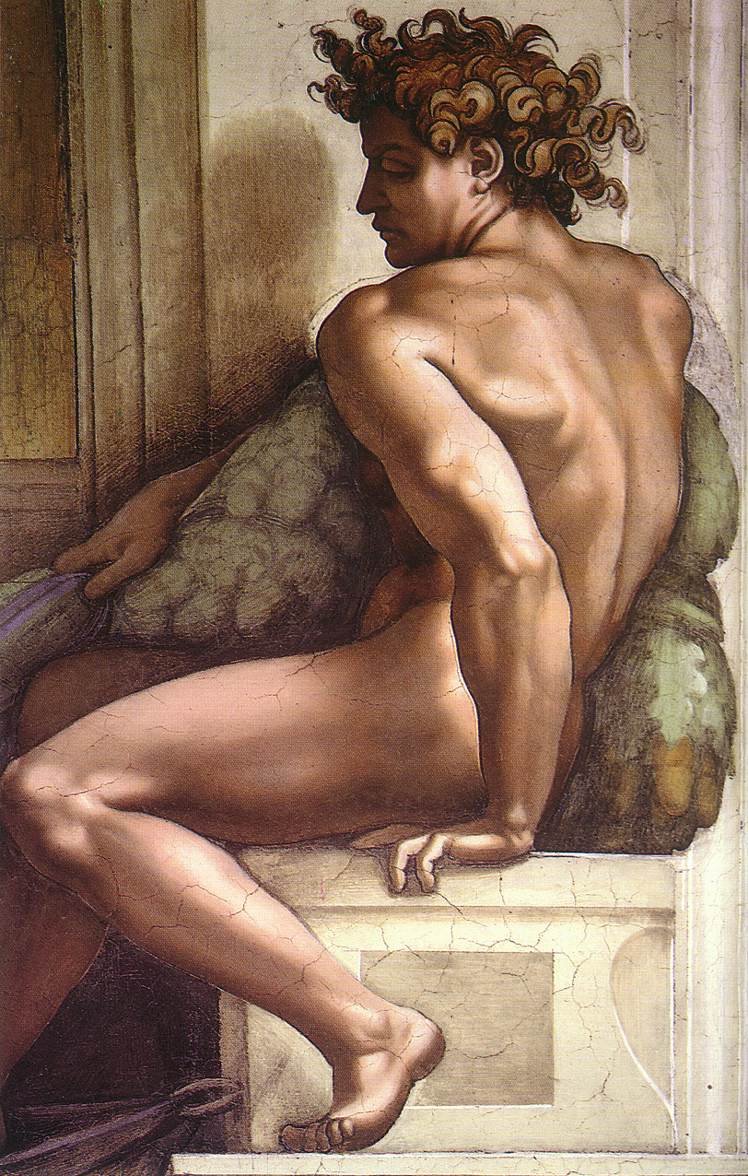

The book’s title, The Agony and the Ecstasy, perfectly characterizes the crushing lows and soaring highs of Michelangelo’s personality. He was euphoric when carving marble and despondent when forced to do pretty much anything else. During creative streaks, he worked for up to twenty hours a day, barely eating and sleeping and going long periods of time without bathing or even changing his clothes. He wore a special candle-holder hat so that he could carve through the night. Aside from enjoying the company of select friends, Michelangelo was anti-social in the extreme. A particularly stubborn man, he argued vociferously with his patrons, who described his temperament as la terribilità (basically, a terrifying awesomeness).

Stone makes it clear that this great artist was temperamental and difficult, even having the character himself admit it several times. That said, the book never judges him. Other authors have compared him unflatteringly to the more extroverted Leonardo and Raphael, so it was nice to finally see Michelangelo’s storied conflicts with those artists from his own perspective. Otherwise, the book is nowhere near as dramatic as the title suggests. I particularly appreciate that Stone provides the necessary context of brutal Renaissance politics without going into the kind of nauseating detail that usually turns me off to reading about this time period.

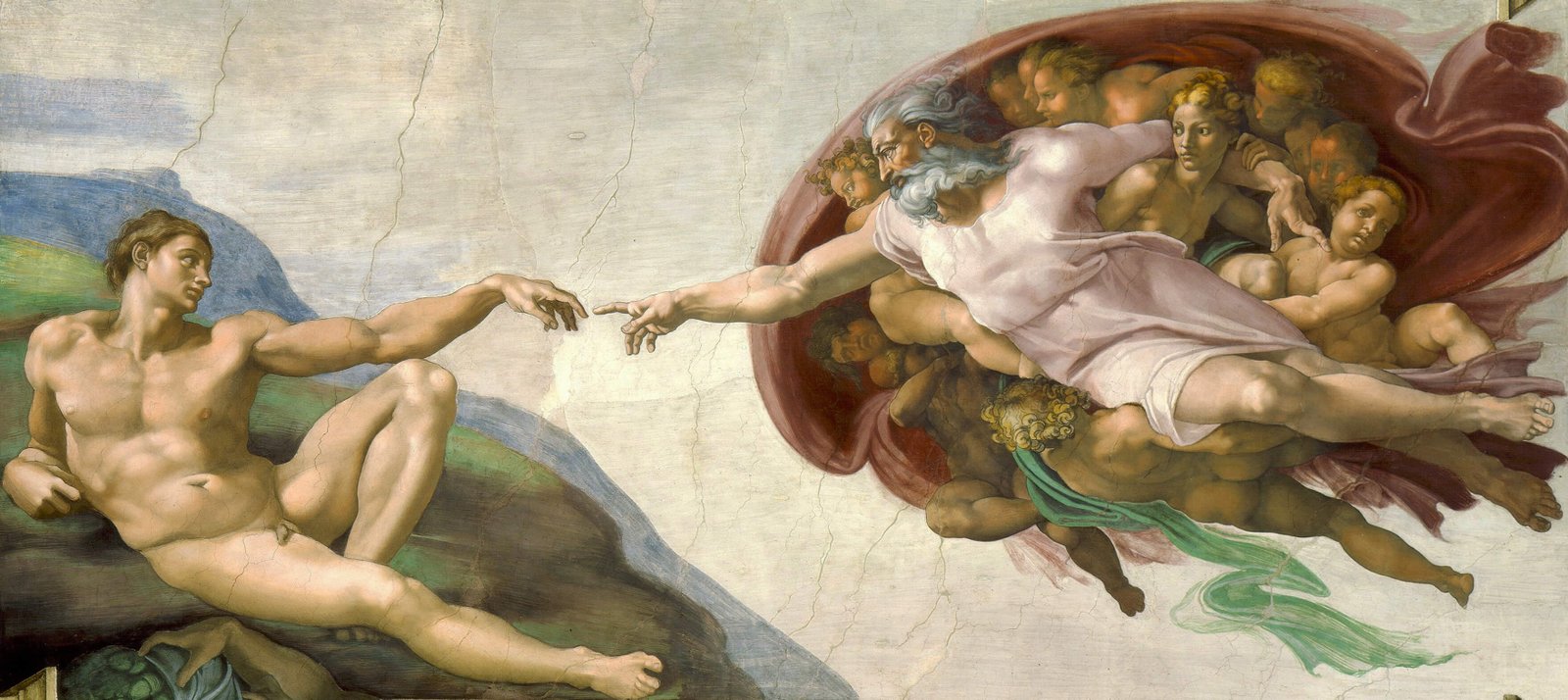

Biographer Irving Stone’s extensive research backs up his portrayal of Michelangelo. Although Stone closes the book by detailing his sources, including all of Michelangelo’s surviving letters and documents, I really have no idea where fact ends and fiction begins. But you know what? I’m okay with that. While Stone’s book definitely isn’t a conventional biography, I believe that it is detailed and authoritative enough to qualify as something more than just pure fiction. The Agony and the Ecstasy made me see Michelangelo as less of a legend and more of a person – a person who lived a very long time ago and accomplished many tremendous things, but a real person nonetheless. I look forward to next time I will stand in front of a Michelangelo artwork now that I know so much more about him.

I highly recommend The Agony and the Ecstasy to anybody who loves Michelangelo, the Renaissance, or good books in general. I was able to borrow a copy from my recently-reopened local library, but I’m sure you could find it in bookstores as well.