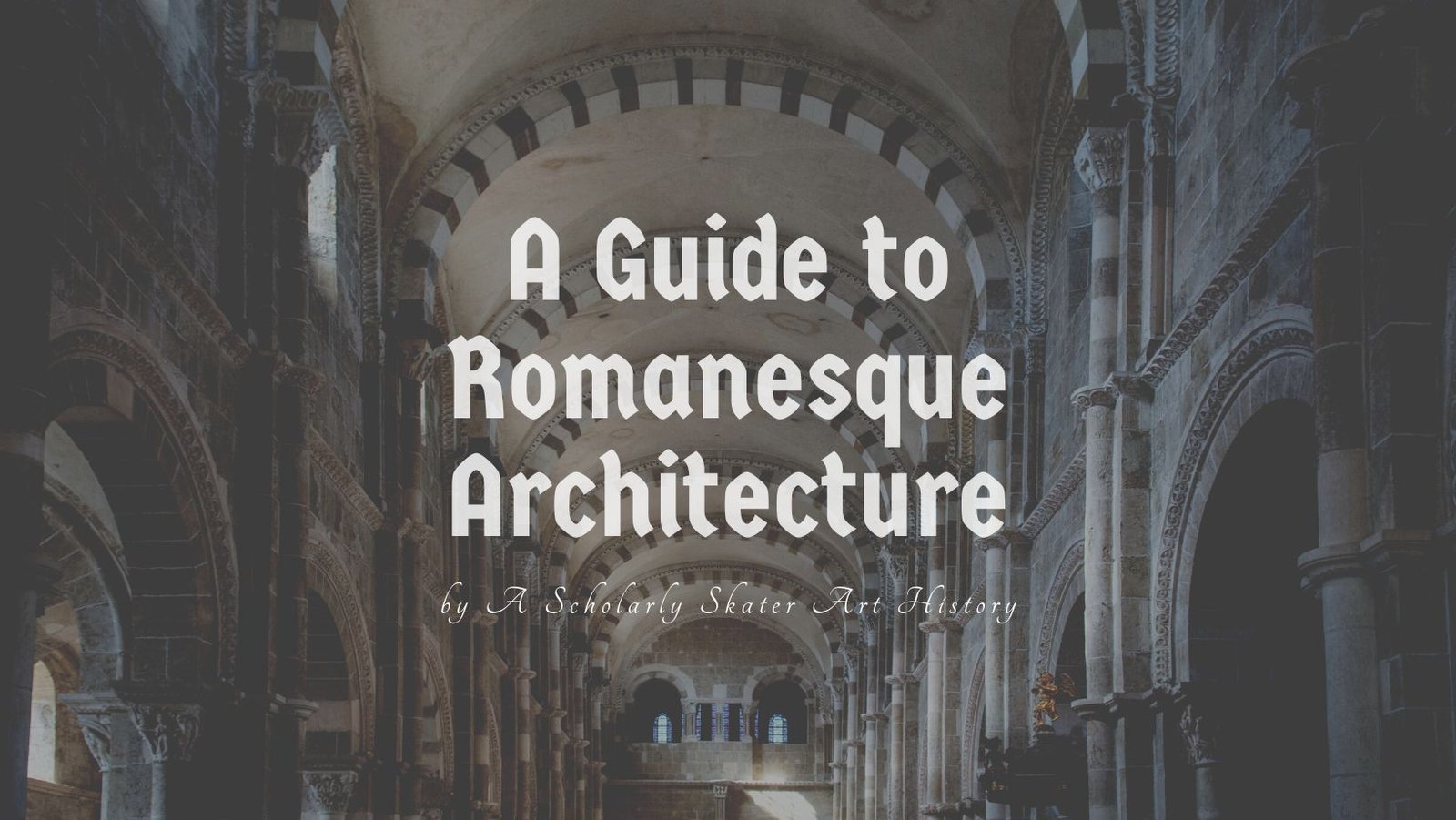

Cover image based on a photo by Jan van der Wolf.

Romanesque was a major style of medieval architecture that was popular in Western Europe in the 11th and 12th centuries CE. It’s the direct predecessor of better-known Gothic architecture. Here’s everything you need to know about Romanesque.

Famous Examples

Romanesque is a style most closely associated with churches, because lots of them were built during this time period and many survive today. However, there were also plenty of other Romanesque buildings, such as castles and cloisters. The churches were generally basilicas, usually with transepts, a series of chapels near the apse, and imposing western entry facades with towers.

Some of the most famous surviving Romanesque churches include Durham Cathedral in England (a sort of Romanesque/Gothic hybrid), churches in Conques, Toulouse, Autun, and Vézelay in France, parts of the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in Spain, and Monreale Cathedral in Sicily.

The Stone Barrel Vault

Romanesque architecture is pretty much exclusively stone construction that employ the rounded arch and barrel vault. (We’ll sometimes see pointed arches and groin vaults, but they won’t become common until Gothic.) Both of these forms hark back to the architecture of ancient Rome, which is how Romanesque gets its name. But while the name and basic forms may be similar, Romanesque aesthetics are quite different from those of its classical namesake.

A barrel vault is the most basic kind of vault. It’s essentially an arch that’s long enough to cover the whole building. In Romanesque buildings, thinner transverse arches often support the vault along its length and provide visual rhythm as you look down the length of the nave. Stone vaulting is incredibly heavy and needs a lot of support, so Romanesque churches are solid buildings with thick walls and massive columns or piers. Hefty buttresses on the exterior and galleries (balconies) on the inside both help to reinforce the building and hold the vault up.

Because of this need for support, there can’t be a lot of openings in the walls. So, the windows tend to be fairly small and interiors correspondingly dark. On the other hand, there’s plenty of wall space to decorate with murals or mosaics. The abundance of walls and relative lack of windows differentiates Romanesque from Gothic, which is all about light.

Romanesque Architectural Sculpture

Architectural sculpture is Romanesque’s major decorative feature, especially the sculpture that appears above, beside, and between the outside doors (portals). There are usually three portals on the western facade and at least one at each end of the transept.

Romanesque portal sculpture is some of the most dramatic, expressive, and fascinating artwork of the entire Middle Ages. It’s a bit rough and static – certainly less elegant and lifelike than Gothic sculpture – but it’s highly effective. Of particular note is the sculpture on the tympanum (the semicircular area above the door) of the center portal of the western facade. It’s usually reserved for representations of the Last Judgement, and they can be pretty graphic.

The capitals above columns are another place for Romanesque sculpture, and unlike the portals, these so-called historiated capitals are not necessarily pious. Their subject matter can include humans, animals, and grotesques behaving strangely and even surprisingly provocatively.

Historical Context

Romanesque architecture coincided with a time of prolific church-building throughout Western Europe. Three major forces contributed to its spread from country to country: the Norman Conquest, monasticism, and pilgrimage.

Normans: When the Normans of northern France conquered places like England (in 1066) and Sicily, they brought Romanesque with them and built a slew of churches in their new lands. It’s sometimes called Norman architecture for this reason, especially in England.

Monasteries: Monasteries (also known as abbeys) are groups of monks or nuns who live, work, and pray together on a property kind of like a college campus. The Romanesque period was a time when many new monasteries were being built, and all the various monastic orders were putting down roots all over Europe and taking their preferred Romanesque style with them when they built new monasteries. In particular, the simplicity-loving Cistercians perpetuated an elegant and paired-down version of Romanesque.

Pilgrimage: During the Middle Ages, religious pilgrimages were wildly popular, as everyone from princes to paupers wanted to visit holy sites and commune with the relics of saints in hopes of receiving healing or other miracles. One major destination was Santiago de Compostela in Spain, which holds the relics of Saint James the Greater (Saint Iago in Spanish). It was so popular that a series of pilgrimage routes sprang up on the way to Santiago from major European cities. Relic-holding churches (often in monasteries) could become stopping points along the route, and these churches would benefit both in prestige and financially, since pilgrims would leave donations as offerings. A lot of these churches were rebuilt in the Romanesque style to better accommodate the flocks of pilgrims who visited them each year. In fact, the idea of building radiating chapels in the east end and an ambulatory to access them from came about from the logistical needs of the pilgrimage industry.

Resources

- Christine M. Bolli, “Pilgrimage routes and the cult of the relic“, in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015.

- Christine M. Bolli, “Fontenay Abbey” in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015, accessed September 8, 2023.

- Carol Davidson Cragoe. How to Read Architecture: A crash course in architectural styles. New York: Rizzoli, 2008.

- McNamara, Denis R. How to Read Churches: A crash course in ecclesiastical architecture. New York: Rizzoli, 2011.

- Valerie Spanswick, “A beginner’s guide to Romanesque architecture“, in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015.

- Valerie Spanswick, “Medieval churches: sources and forms“, in Smarthistory, August 8, 2015.

- Stephenson, David. Heavenly Vaults: From Romanesque to Gothic in European Architecture. Princeton Architectural Press, 2009. This is more of a coffee-table book than a reading book, but it contains spectacular photographs of Romanesque and Gothic church vaults.