Welcome to 31 Days of Medieval Manuscripts, a month-long series introducing the fascinating and brilliant world of medieval illuminated manuscripts.

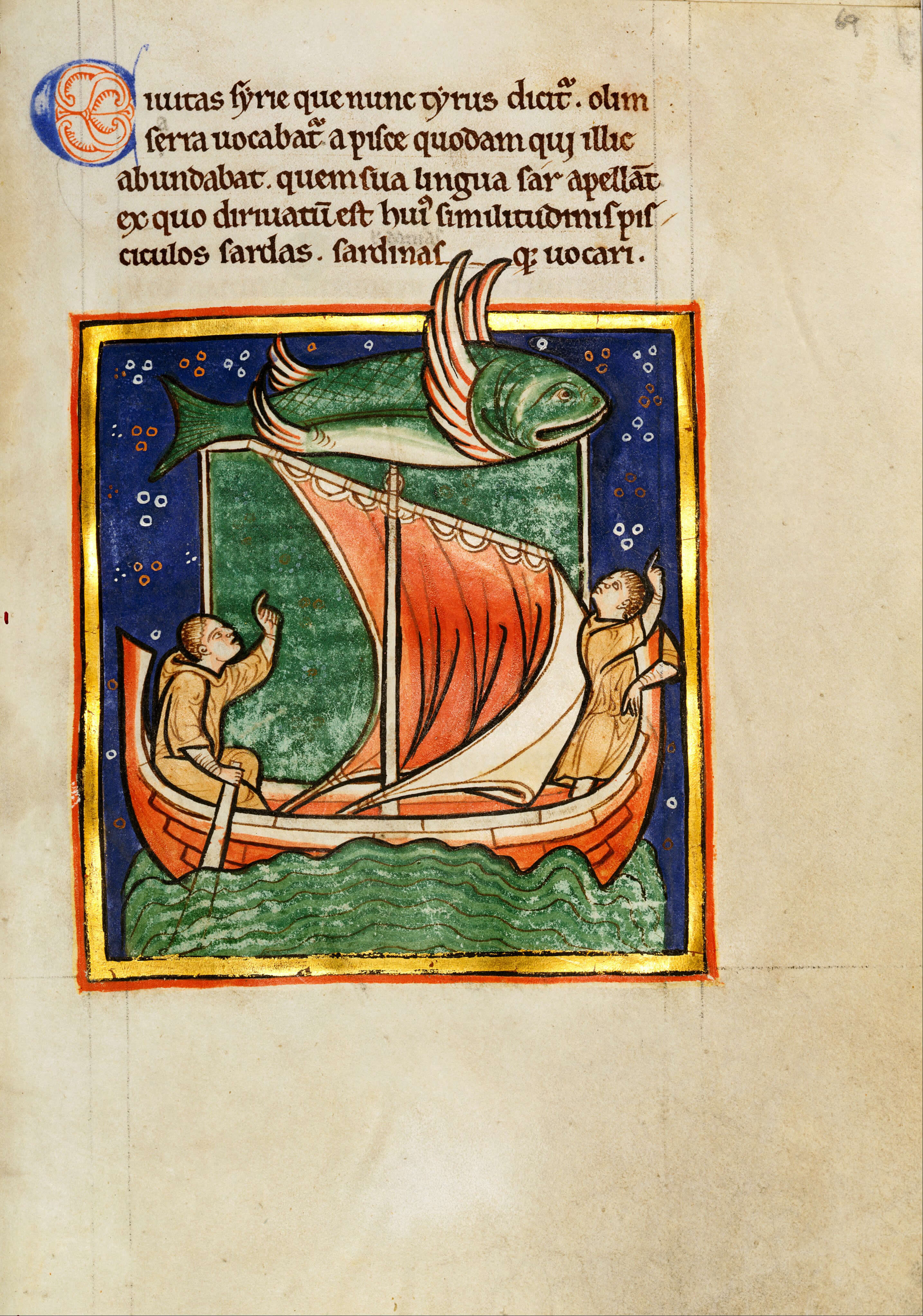

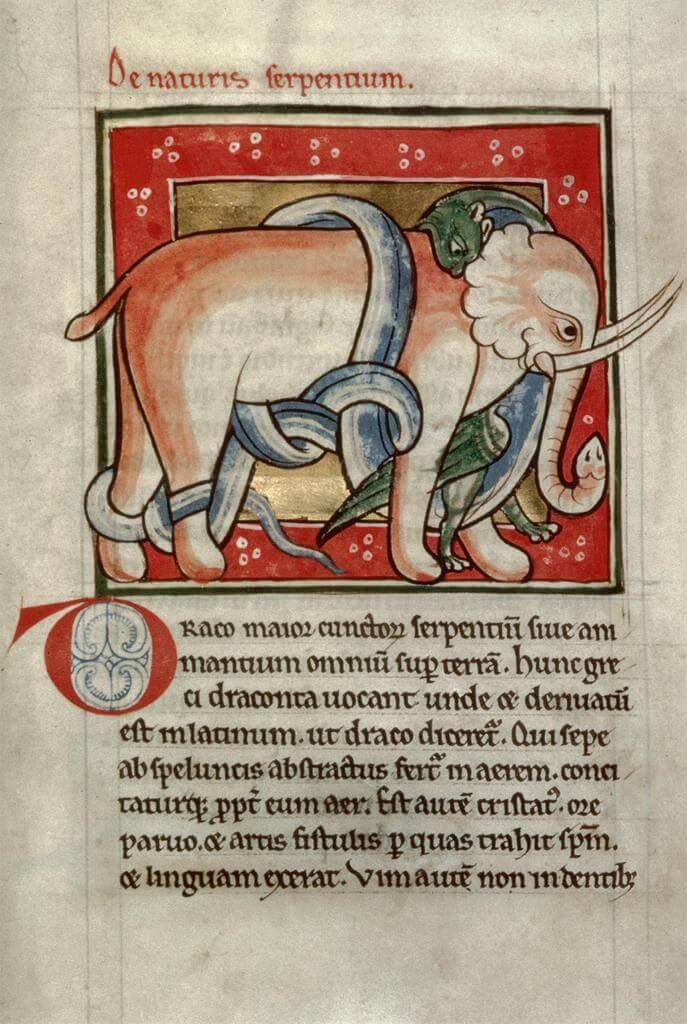

Bestiaries are among my favorite type of medieval manuscript. Simply put, bestiaries are books of animals, containing illustrations and descriptions of each creature. With a mix of real and imagined creatures, quirky illustrations, and “facts” that are more like myth and allegory, bestiaries are endlessly fascinating and charming. These books are far more like something out of Harry Potter than a zoology book, and it’s easy to see echos of bestiaries in many modern-day fantasy stories.

Bestiaries

Deriving from a variety of classical and Christian, sources including the then-authoritative 2nd century CE Greek Physiologus, bestiary texts illustrated and described various creatures. The focus was more on providing moral lessons and Christian allegories than on scientific information we would consider to be factual today. Based on their supposed attributes and behaviors, some animals were seen as good, with symbolic qualities like heroism, loyalty, etc., while others were thought to be greedy, lustful, and things like that. These reputations, let’s call them, were often based on some odd beliefs about animals’ habits of eating, hunting, producing offspring, and more. Not all the animals included are even real; creatures like phoenixes and sirens appear alongside beasts like dogs and lions.

It’s a matter of some debate how much bestiaries’ medieval audiences believed in the factual truth of these texts and how much they recognized them as symbolic even at the time. After all, these books generally include many creatures not common in Europe, so bestiary writers and readers would not have had first-hand experience with all of them.

The bestiary was not a single, uniform text but rather had multiple possible variations on a similar theme. It’s also not solely a European phenomenon, since there were also books of creatures from the Islamic world, often using similar source material.

The Worksop Bestiary

The Worksop Bestiary (Morgan Library, MS. M.81), is a late-12th century English bestiary named for the town in whose monastery it once resided. Worksop is among the one or two earliest of the 62 surviving illustrated medieval European bestiaries and includes over 100 creatures.1 It is full of colorful and charming illustrations, which are vivid but not especially naturalistic. Just as with animal depictions elsewhere in medieval art, it’s sometimes difficult to even tell which animals is being depicted, since they are shown with physical attributes they don’t have in the real world. The crocodile looks like a mammal, for example, and some of the snakes have legs and wings.

Medieval bestiaries still hold a certain fascination today, and in my opinion, the images are a major reason for their enduring appeal. All in all, the unbelievable facts, quirky images, and inclusion of real and imagined creature side-by-side make bestiaries perennial favorites. They are both relatable and fantastical at the same time – familiar and strange in equal measure.

You can peruse the entire Worksop Bestiary here at the Morgan’s website.

- Jackson, Deirdre. “Into the Wild: Medieval Books of Beasts”. Video. New York: The Morgan Library and Museum, September 30, 2020. Accessed October 10, 2023. ↩︎

For further reading, see:

- Badke, David. “The Medieval Bestiary: Animals in the Middle Ages” (bestiary.ca).

- Benton, Janetta Rebold. The Medieval Menagerie: Animals in the Art of the Middle Ages. New York: Abbeville Press, Inc., 1992.

- Schrader, J.L. “A Medieval Bestiary“. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin Vol. XLIV, No. 1 (Summer 1986).